veeral does data

The Monty Hall Problem

17 April, 2020

Introduction

This post isn't exactly "Data Science". However, it does deal with math and probability, and is an ideal example of statistics and probability rebuking seemingly simple intuition. Here's my take on the Monty Hall Problem:

What is the Monty Hall Problem?

The Monty Hall problem is based on a game show situation. Let's start by explaining the puzzle:

- There are THREE closed doors, two of the doors have goats behind them and one has a new car

- The contestant chooses a door hoping to pick the door with the new car

- The game show Host then checks the other two doors and opens one of them to reveal a goat

The Host then asks the contestant if he or she would like to stick with the door originally chosen, or switch to the other unopened door.

Stay or Switch?

Ok, you understand the puzzle. Now, what should the contestant do? Stay with the originally chosen door, or switch to the other unopened door? Does it matter?

Intuition tells us that it does not matter. Either way, the contestant has to choose between two doors, giving a 50% chance of getting the car whether you stay or switch, right?

As alluded to in the intro, intuition loses to math here. According to the math, the contestant should ALWAYS SWITCH.

The Monty Hall Solution is WRONG!

Well... that was my first thought. It just doesn't make sense. How would your odds possibly be higher by switching? How would it not be a 50/50 choice either way?

It turns out that if you switch, you actually have a 66.6% chance of winning the car. This statistical illusion is rooted in the information gained when the Host reveals a door with a goat.

Don't believe it? Try it for yourself here. Either pick doors and see how often you win, or run the simulator and check out the results. The numbers don't lie!

Let's take a look at the math and see where our intuition goes wrong.

The Monty Hall Solution: The Math Explained

Let's start at the beginning.

- Let's say you are the contestant. You have no clue which door has what. You randomly choose a door and have a 33.3% chance (1 in 3) of choosing the door with the car behind it

-

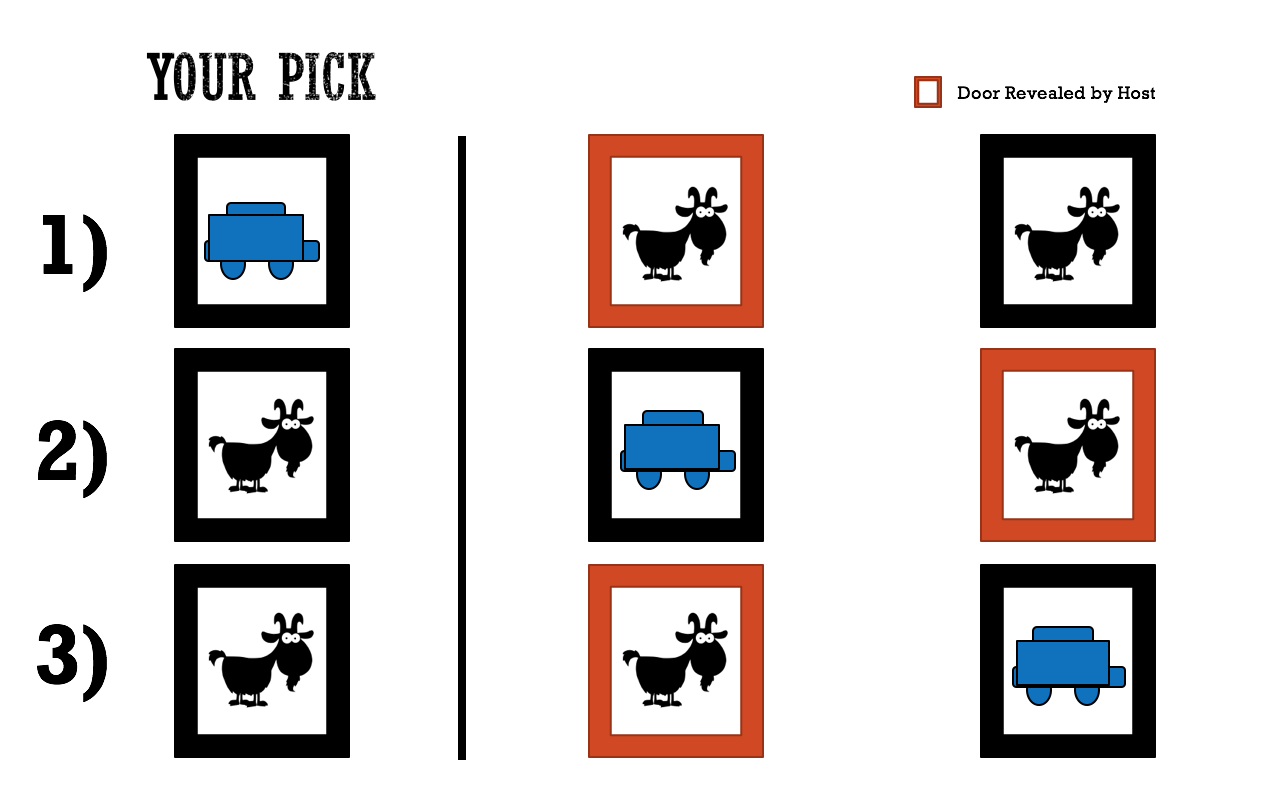

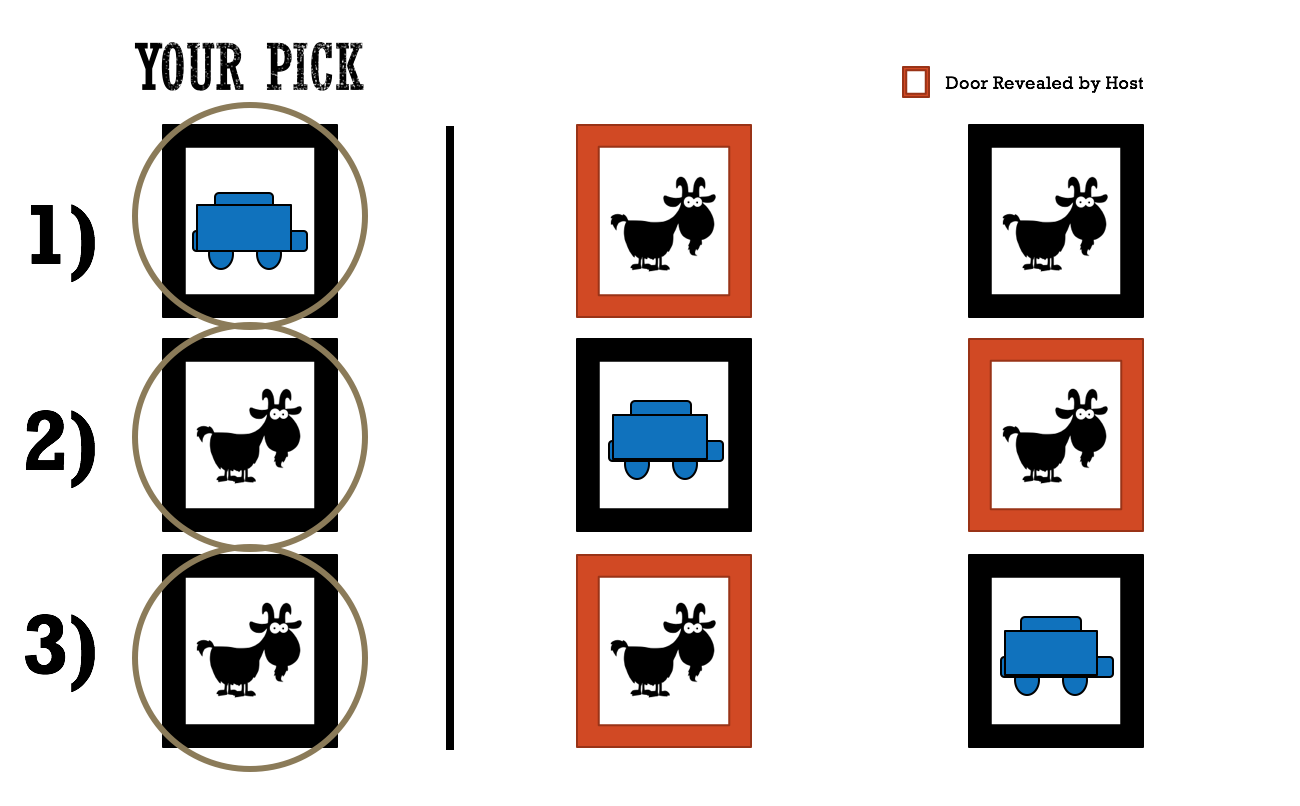

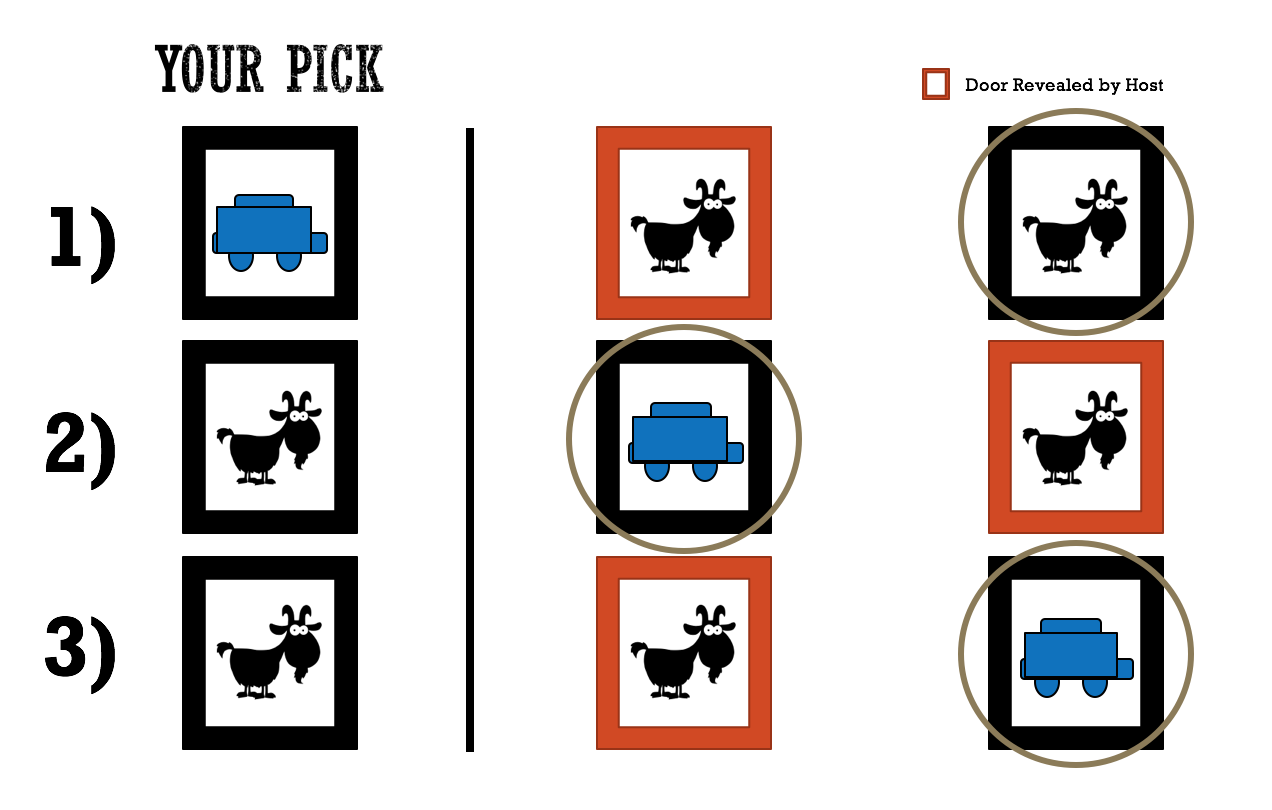

Three situations arise:

- You choose the car

- You choose goat 1

- You choose goat 2

- The Host then reveals one of two remaining doors with a goat behind it

Option A: Contestant Stays

Situation 1a: The contestant chooses the car

- The host reveals either of the goats behind the other two doors

- You decide to stay

- You win the car!

Situation 2a: The contestant chooses goat 1

- The host reveals the door with goat 2

- You decide to stay

- You do not win the car

Situation 3a: The contestant chooses goat 2

- The host reveals the door with goat 1

- You decide to stay

- You do not win the car

Option B: Contestant Switches

Situation 1b: The contestant chooses the car.

- The host reveals either of the goats behind the other two doors

- You switch doors

- You do not win the car

Situation 2b: The contestant chooses goat 1

- The host reveals the door with goat 2

- You switch doors

- You win the car!

Situation 3b: The contestant chooses goat 2

- The host reveals the door with goat 1

- You switch doors

- You win the car!

The contest wins just 1 out the 3 possible situations if they stay with the original choice, and 2 of 3 situations (66.6%) if they choose to switch!

Where the Odds Change

Ok, you've seen the probabilities, the math, and the diagrams. You accept that the contestant should switch. But how is this statistical illusion created? What causes the odds to change, and where does the 50/50 choice between two doors turn into a 66.6% chance of winning if you switch?

The change in probability occurs when the Host (who knows where the car is) chooses to open a door with a goat. This creates a new mathematical situation by which the Contestant can make a choice.

When the Contestant first chooses a door, he or she has no information. Three choices and no information leads to a mathematically random choice, and a 1/3 probability of selecting the car.

When the Contestant is given the choice to switch, there is two choices. However, unlike the first time, there is mathematical information to be used in this situation. The concrete information that the Host filtered out a goat gives you an extra 16.6% of chance of winning and turns a random 50/50 guess into an clear choice to switch doors.

Summary

Here are the key steps to understanding the Monty Hall puzzle:

- Information is key. A two-choice problem is not necessarily 50/50 unless it is completely random

- The Host's knowledge-dependent filter of the choices introduces new information

- Math always wins